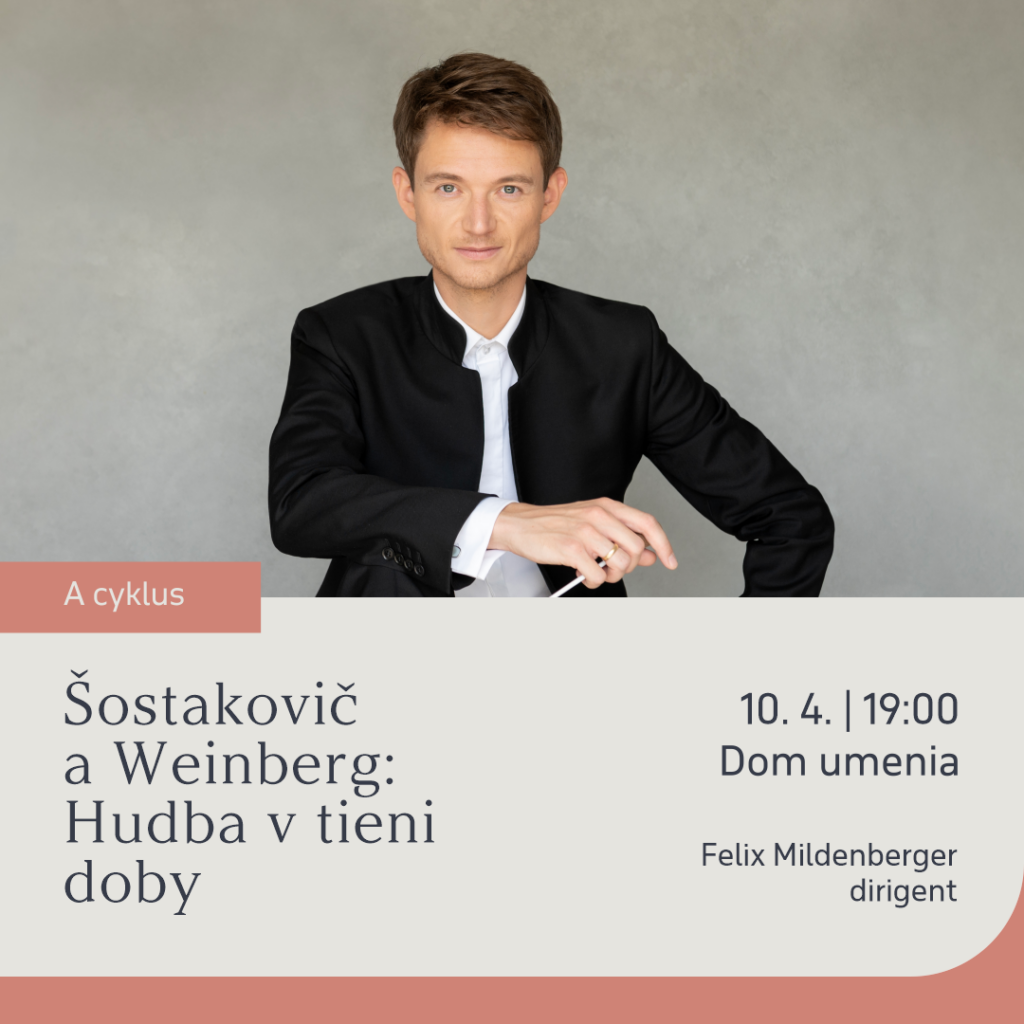

„One thing about masterpieces is that they are timeless. And so this is definitely the case for Shostakovitch’s music,“ says conductor Felix Mildenberger to our online magazine. Mildenberger will conduct the Košice State Philharmonic for the first time at the final concert of the Allegretto Žilina festival. The audience can expect a challenging but at the same time wonderful program with the evening’s exceptional soloist – Dmytro Udovychenko.

You studied conducting at the Freiburg University of Music and later at the University of Performing Arts in Vienna. In addition, you gained experience in master classes with conductors such as David Zinman, Paavo Järvi, Neeme Järvi and Markus Stenz, as well as Bernard Haitink. I am particularly interested in Maestro Haitink, whom we said goodbye to in 2021. What did he mean to you? What did you learn from him?

Bernard Haitink was a fascinating conductor and – like many of the other maestri that I had the chance to meet, work with and learn from – he had a strong influence on my development as an artist. However, like with all those great conductors it goes beyond what words can express what they taught us or what their secret was.

I was very lucky to be able to study with Bernard Haitink at a young age, to observe his rehearsals and to assist him with the London Symphony Orchestra and Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra Amsterdam. He definitely was a master of concentration. He didn’t „do“ much, he didn’t speak much. He let his body „speak“. The things he achieved with orchestras, he achieved mainly through his eyes, his very strong suggestive aura and through his sheer presence on stage.

For a young conductor this is not necessarily something that you can easily adopt, because it requires decades of experience. But it is something that from the first moment on strikes you as extremely fascinating and therefore becomes a life goal as a conductor. That’s the beauty of learning, you may not always immediately be able to adopt and implement something right away. But these lessons, advice, insight and impressions stay with you as you grow and go your own way. And then they come back at the right moment when you are ready to fully understand and inherit them and make them your own. After all, every conductor’s body and mind are different, that’s why teaching conducting is so difficult. There are basic things you can teach, but the very essence of it is something that you need to experience and grow within yourself like a plant.

Maestro Haitink used to have a score in front of him, but he did not turn the pages. In his 80ies he knew every note. But the members of the orchestra looked at him very often. Should the conductor be a natural authority to achieve control over the orchestra?

Natural authority is definitely better than artificial authority, actively built up through pressure, hierarchy and power. And actually the natural one is the only form of authority that will work between a conductor and an orchestra on a long-term basis. Because in the second case you will get an orchestra that tries to do what you want because they are forced or because they fear consequences. Whereas in the first case you will get an orchestra formed of individuals that want to contribute their part to the whole because they feel respected and because they want to follow you.

I guess that’s also something to mention when people wonder what talent in conducting is about. Some people just have this natural authority, this natural way of making people wanting to follow them, by inspiring rather than imposing.

This in my opinion also should apply to politicians and all forms of leadership, by the way.

The premiere of Symphony No. 3 by Polish composer Mieczysław Weinberg will be held at the festival Allegretto Žilina. This author has been very popular in recent years, and we are gradually discovering his emotionally rich work. Why do you think it is relevant today?

When I first heard Weinberg’s music a few years ago, I couldn’t believe I hadn’t heard of him before. And I still can’t believe his music has been neglected until recently. His œuvre is so rich, his style is so unique, his music so expressive and powerful, it absolutely has to be rediscovered and presented to audiences more often!

The fact that Weinberg and Shostakovitch were close friends and exchanged their works before publishing them, says it all. And with him who throughout his whole life felt like he didn’t really belong anywhere, his biography is certainly something to relate to nowadays.

Apart from the fact that his compositions are extremely well made, masterly instrumented and of utter musical expression.

Weinberg wrote this symphony between March 1949 and June 1950 during the „anti-formalist“ purges instigated by Andrey Zhdanov. Do you think he wrote his symphony under the pressure or he incorporated the folk material into his music in the sense of the tradition in Russian/Soviet music?

It is hard to guess what motives Weinberg had when writing his 3rd Symphony. On the one hand, he definitely must have felt the pressure and restrictions from the regime. But I am sure he also must have had a special affinity for the folk music of the countries he lived in.

On the one hand the music in the first movement is very serene and on the other nervous and culminating. How do you understand those contrast in this movement?

Music lives on contrast. It is one of the main ingredients of masterpieces, if not the essence. Most composers put part of themselves, their souls, their emotions, their feelings, their thoughts into their music. Those feelings will never be one-dimensional. But they will always bring different facets. The presence of both makes each of them stick out even more. They benefit from each other’s presence. It makes beautiful, dolce passages shine even more whereas dark, cold or loud parts will have an even stronger effect. In other words, when Weinberg confronts serene and calm music with striking, sharp and brutal music, both appear even stronger in their own character. The amazing C major ending of the 3rd movement wouldn’t be that touching and warm and bright if as listeners we hadn’t already gone through a long passage of c minor, a culmination with loud, dissonant chords and – just before the end – a dark and extremely „cold“ d flat minor chord, played by stopped horns.

The scherzo again quotes a folk tune. This time we clearly hear polish mazurka. It is a demanding piece that must be played with danceability, ease, purity and precision. Are there sometimes things in music that seem simple that are the most difficult? For example, if we take Chopin’s Mazurkas, they also seem technically easy, but they are often very demanding for musicians…

Yes, absolutely!

The true masters (in music, but also in painting and other arts) knew how to make things look or sound easy. However the more you study it, the closer you get, the more you will find out how many details there actually are and how complex they are in a way.

If we think of Mozart’s or Schubert’s masterworks, that for me are amongst the most touching of all music. Yet, they are the perfect examples of the art of simplicity. However, being (or seeming) simple doesn’t mean it’s easy! Mozart’s and Schubert’s music are among the most difficult ever to perform. There is a reason why Mozart’s music is part of every audition.

Or if we think of (ballet) dancers. Their performance always has to look easy, elegant and effortless, yet it requires the highest level of body control, training and perfection.

The slow movement is beautiful. It is full of pain and suffering. Do you think that this is the core of the symphony?

It definitely plays a major role in the symphony and may be key to understanding it as a whole. With its dark and slow character it is also an important counterpart to the preceding scherzo and the following finale that are both bursting with energy and drive.

How would you explain that the movement is finishing with C major?

In the slow movement Weinberg uses the melody of a Polish folk song, that describes a young girl working on the fields and waiting for the sun to set so that she can finally rest. Some people say that the C major chord is the moment when the girl dies.

I personally don’t think it necessarily needs such a precise story. The music speaks for itself! Like I said earlier, this simple and clear C major chord has an enormous effect after all the dark, heavy, depressing music that precedes. It has such a liberating and calming power and therefore stands for itself. It could also be a glimpse of hope. A ray of light in total darkness.

The finale is close to Weinberg’s friend Shostakovich. What material is the composer developing?

In the finale of the symphony Weinberg develops a motif that the listener will recognize from the first movement. More precisely the third theme, in the first movement presented as a cantabile and espressivo melody in D major, becomes – slightly adjusted, but starting from the same material – a powerful, but sharp, relentless and almost threatening, war-like fanfare in b minor, played marcatissimo.

Towards the end of the finale, at the very climax of the movement, Weinberg brings back the initial main theme from the first movement, in augmented form and thus creates a closing circle around the symphony as a whole.

Violin concerto by Shostakovich is also a composition full of emotional depth. So are we going to get two emotionally powerful works during the concert in Žilina?

Yes.

This concert will also remind us of a sad piece of history. Could we call it as a historical documentary about the Second World War?

I think it is a very subjective depiction of what life during Second World War and in a regime meant for many artists and people in general. Maybe it was like a musical diary and self-therapy for Shostakovich and Weinberg, a necessary way of canalising their feelings, thoughts and emotions which for so long they weren’t able to express verbally.

In next movements the composer connects lyrical moments with drama. Passacaglia is a masterpiece and the final Burlesque is a picture of a marked society, which has an almost demonic character in its expression. As an artist, do you feel any similarities between the image of the world of that time and today? Is Shostakovich’s music timeless?

One thing about masterpieces is that they are timeless. And so this is definitely the case for Shostakovitch’s music. Even without linking it to specific events and situations in our world nowadays his music will always strike or move the listener, it will evoke very clear expression, emotions and atmospheres. And for the ones that know about his life and the circumstances in which he created his works, listening to his music can be like traveling back in time and „witnessing“ through his eyes what he had to go through.

Overall, the concert places high technical demands on the soloist, as well as the orchestra. Is it mentally challenging to perform such works? And despite the difficult topics – are you looking forward to a concert with the Košice State Philharmonic and an exceptional soloist?

Yes, of course!

Zuzana Vachová

Photo: felixmildenberger.com

SLOVAK VERSION OF THE INTERVIEW