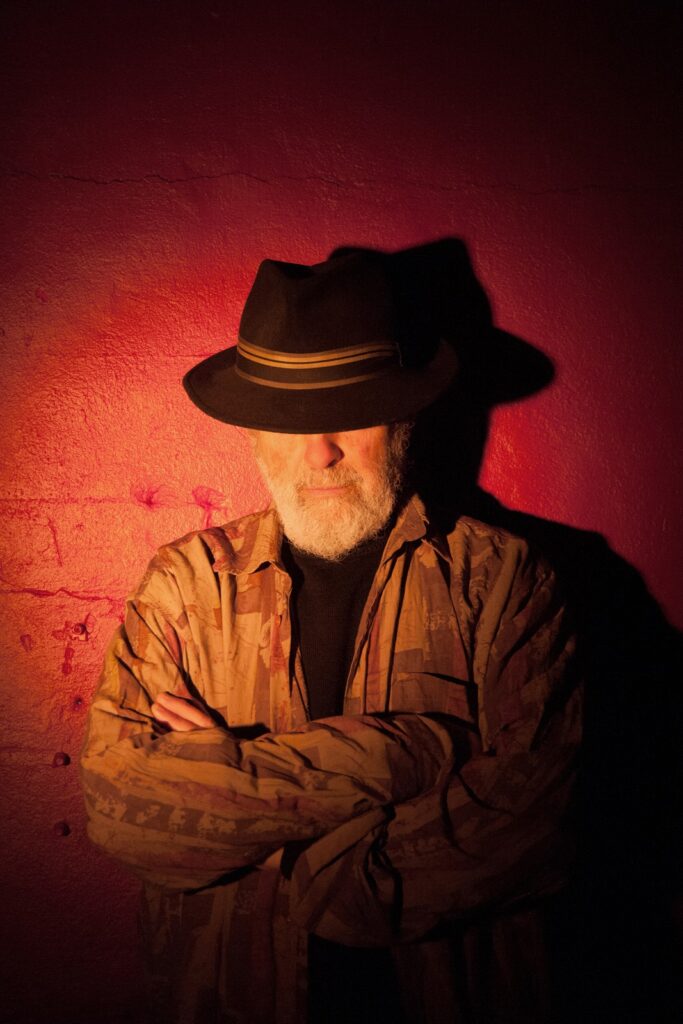

“I must say that seeing things first is not an advantage, because one often has to suffer and is not understood. My ideas often provoked scandal, and then became fashionable later on…” says leader and founder of Nomadic Piano Project Antoni O´Breskey for our online magazine.

You started to play piano at the age of three. I think about what I did at that age (started to play piano at 6 like all “normal” kids), what today’s three-year-olds do. I guess a person has to grow up in an environment, to be in contact with music already at the prenatal stage, in order to start playing the piano at the age of three, right?

Yes, absolutely, but I’ve been very lucky, especially being born in Italy, where I often say I was born ‘by accident’, even though I love some parts of Italy very much!

Italy was ranked 64th in the world for musical culture, even though it is world-famous (because we refer to Renaissance Italy, which is long gone, and in any case we are always talking about western musical culture, which in these centuries has taken over from other cultures that are often much more important, in Debussy’s opinion too!).

I quote here one of his writings, probably kept very much hidden by the Conservatories and Academies:

“There were, and there still are, despite the evils of civilization, some delightful native peoples for whom music is as natural as breathing. Their conservatoire is the eternal rhythm of the sea, the wind among the leaves and the thousand sounds of nature which they understand without consulting an arbitrary treatise. Their traditions reside in old songs, combined with dances, built up throughout the centuries. Yet Javanese music is based on a type of counterpoint by comparison with which that of Palestrina is child’s play. And if we listen without European prejudice to the charm of their percussion we must confess that our percussion is like primitive noises at a country fair.”

Claude Debussy

In my parents‘ time, however, there were still very interesting realities, jazz ones, even the famous Sanremo Festival, which in the last thirty years has become a circus in bad taste, at the time hosted interesting realities, bordering on Jazz.

Not only was I in contact with music from the moment I was born, but with music that was quite rare and special, namely early jazz. My uncle Lanfranco Magni, a drummer (who during the war even played at a secret jam session in Florence with Louis Armstrong), my mother Lidia Magni a dancer, and my father Giorgio Breschi, a pianist, were non-professional musicians (my uncle a dentist, my mother a housewife, my father a merchant)… exactly like the first Jazz great musicians in New Orleans!

My father learnt Jazz as a self-taught ‘by ear’ on the sly, listening to (forbidden) American radio during the war, because at the time Mussolini had banned Jazz in Italy because it was ‘American’ music! Lucky on the one hand, but also unlucky on the other, because my father was always opposed to my musical career as a professional. This battle was perhaps also good karma, because it made me realise that there was some truth in wanting to hinder my career as a musician, because then I also hindered it myself!

On the one hand I fought with my family to ‘be a musician’, on the other hand I fought against myself, rejecting many times the commercial success, which often came to me in huge forms, but it scared me, and I realised that indeed professionalism can destroy music…

When you grew up, your studies continued at the Luigi Cherubini Conservatory in Florence, but what interests me is the combination with the trumpet, which you also studied. It’s an unusual combination. Was your interest in the trumpet, on which we see you playing today, in addition to the piano, also influenced from the fact that you were interested in jazz?

Yes, I studied at the Conservatory of Classical music in Florence, and it was not easy, I was hindered, and not a little, because I also played Jazz, which was considered an ‘inferior’ music. Today, Jazz has become part of the studies at the Conservatory of Classical music, but not because the Conservatory has opened up to this music, but because it is Jazz that has lost much of the spontaneity and identity of its origins, and has become academised on the one hand, and commercialised on the other! When I was 16, I founded the Firenze Jazz Association with four other music critic friends, to bring the spirit of jazz back to this city, which had disappeared since the post-war period. We also hosted Duke Ellington in the small town of Prato where my mother was born. Duke was refused at the time by the Teatro Musicale dell’Opera in Florence because Jazz was not considered music worthy of being in a theatre.

Regarding the study of the trumpet, nothing in my life has been calculated, my whole life has been a continuous mix of adventure and misadventure…and a constant struggle!

My father didn’t want me to go to the Conservatory, he just wanted me to study at the classical gymnasium, and I kept repeating the year at the gymnasium, fighting to be able to make music. At one point I was so sick that I ended up on psychiatric drugs, in the military psychiatric clinic (at the time of the military call!). At that point my father realised that maybe he had done something wrong in obstructing me so much and decided to enrol me at the Conservatory, but at that time they had no place for piano, only trumpet. The trumpet had always fascinated me so much, so I was happy to start with that, and then continue with the piano when space became available. I am not a ‘professional’ trumpet player, but because of that perhaps, it gives me a lot of joy to play it.

Is jazz the genre that can accept various other musical influences? You yourself are proof of that. You prove that music has no boundaries. In your opinion, what makes jazz special?

Of course, there is no music like Jazz that has absorbed so many different musics, creating a crossover…but beware! Even classical music in the beginning absorbed so many musical influences, making them universal, but then unfortunately it also globalised them… and this also happened to World Music, and to Jazz… My idea of crossover, which today is very fashionable, is not just adding a drum or a bass to a classic orchestra or singing with classic opera voice a gospel or an Irish sean nos. Crossover, as I will explain more later, existed already especially in Irish traditional music but also in classical music. And Jazz was born from a crossover! Classical composers like Bach, Bartok, Stravinsky, Debussy, Ravel, have created a big crossover, the problem is that especially from the middle of the nineteenth century very few are the performers who make you feel this crossover. It is not a coincidence that they say that with pianist Cortot “an era has ended”. The meaning and the importance of crossover for me, especially today, should not be just an aesthetical dialog between different styles of music, which have been considered opposed, but to use those values that traditional music still has, and through this exchange try to give back some of those to the “Western Music” (both Classical and Jazz).

It is not just only about what you play or how you play, but how you live music and what you do with it: communication, participation, sensuality, dance, rituality, and more…all aspects which traditional music still has and the Jazz of the origins had, in fact it was not called Jazz but ‘tradition’! And the ultimate example of experiencing music in this way, and not just passively seeking it out, is in my opinion the session in the pubs of Ireland, which is something extraordinary in the western world, but also unique in the world.

We can immediately tell from your playing that you are a classically educated musician. The listener can distinguish technique, harmony, the way you play the chords, phrasing of melody and your position of hands. But what about the exceptions that exist in jazz? Such as Thelonius Monk, for example. They are two opposites, but both are charming to me. Does jazz also mean freedom for you? And I am not asking this question only in the sense of improvisation…

Yes, I had classical training but always with great struggles and difficulties! My hands, for example, were very small, I think few would have tried to tackle a piano career with my hands…then I always had pains, I did many types of work that I consider essential to live a better musical career too, such as hoeing the land, cooking, even professionally, and teaching… I used my hands in a thousand ways going against what my teachers told me.

The classical approach I had was my contradiction, it always made me suffer so much, most of the teachers did not understand me, only a few enlightened teachers saved me, and made me succeed in getting my diploma. I kept repeating the harmony class, I who would be a composer! I couldn’t stay within the rules, until one day, at the umpteenth exam, a particularly open teacher, the great accordionist Salvatore Di Gesualdo, understood me.

I had got it all wrong, but he made me improvise and then said in front of everyone: Despite the exercise being all wrong you did much more than I asked you to, the school always flunks the best, but I won’t flunk you this time! And thanks to him I was able to finish my piano diploma!

Yes, for me Jazz means freedom if it is not academised or over-tempered and clean. And when it does not lose the irony and spontaneity of its origins. Just look at the faces of those black musicians from the origins of jazz, most of whom had Irish ancestors (and you can also see this in their surnames) their big smiles and their facial expressions! And not only did their faces laugh or cry, but the sounds of the instruments were expressive, sometimes the trumpets or clarinets laughed, sometimes they cried, but they were always alive and never aseptic. I suffered of discrimination even in the Jazz academic environment. It was a good thing that I was saved later by the arrival of pianists like Keith Jarret, with whom I have often been compared. At the beginning, when they told me that I played in his style, I didn’t even know who he was! Then I got to know him, I liked him and took him as a ‘maestro’, I especially loved his early works. I remember in 1985 the Spanish TV programme Fin de Siglos announced me as ‘the new Keith Jarret of the Mediterranean’. But my greatest myths in Jazz pianism are all the (often) unknown honky-tonk and boogie woogie pianists and the first Jazz pianist ‘maestros’ of my father Teddy Wilson and Errol Garner. My other great myth, which I consider the most important teachers in my music, they are not pianist and they are often not professional musicians, they are children and old people playing fiddle, pipes, flutes, singing and dancing in the pubs in Ireland, and the flamenco musicians and dancers in the ‘peña flamenca’ in Andalusia.

To come back to the concept of freedom, Jazz didn’t need a style called ‘free Jazz’ , because Jazz’s main feature was freedom already! So in my opinion this invention shows us the beginning of the decadence of Jazz, which tries to rebuild rationally the instinctive and natural elements that had been lost. This doesn’t mean that in the same free Jazz style and after that until now didn’t exist true musicians that are still following the path of the tradition, and I can hear that more now than 20 years ago, some rebirth of the Jazz spirit with the reconnections with the common roots. Indeed, Thelonious Monk, and then Dollar Brand, are great examples of true freedom in Jazz!

You founded the International Folk Group which became the Whiskey Trail group. The name refers to the Irish emigrants who went to America. According to you they met with African people and gave birth to jazz. And we can hear also a musical prove (Irish Meet The Blues and lots of others) where you combine these two cultures, very sophisticatedly on the one hand and on the other, it sound very natural. How can you prove it in theory and history? Which elements of the music are Irish and which African? Let´s take an example – blues…

After years of having this intuition of the meeting of African and Irish culture in America, I finally found a very interesting article, excerpted from Michael Ventura’s book ‘Shadow Dancing in the U.S.A. Not many people know that Africans were not the only slaves in the West Indies. Michael Ventura explains very well in his article „Hear that long snake moan“ how Jazz was born primarily from the meeting of the Irish slaves (80.000 were deported by Cromwell in the 17th century) and the African slaves, and we must not forget the Amerindians who lived in the Mississippi area.

He also explained how jazz came to life from a ritual, the West Indian voodoo (originated by a synthesis of West African and Irish pagan influences).In their beliefs and symbology the pagan Irish were closer to Africa than to Puritan England. In 1817 in New Orleans this ritual (basically performed with drums and dance) was forbidden because of its potentially revolutionary power, and only allowed publicly on Sundays in Congo Square, where the police could control them. The people began passing by and stopping to observe, enjoying the music, then offering their money,,..the ritual gradually became show… As Ventura explained in his article, the Africans and the Irish slaves would have their revenge:

“Jazz and rock’n’roll would evolve from Voodoo, carrying within them a metaphysical antidote for both the ravages of the mind-body split codified by Christianism and the onset of technology. The twentieth century would dance as no other had, and, through that dance, secrets would be passed. First North America, and then the whole world, would – like the old blues says – “hear that long snake moan.”

The syncopated rhythms come mainly from Ireland/Scotland… then of course also from gypsy music. Jazz dance, the so-called Jazz tap dance, is, in my opinion, 70 % Irish, 20 % flamenco and 10 % African… It is known now that Beethoven anticipated ragtime in his sonata n.32 op 101, but no one in my opinion knows the real reason why. Why did he anticipate ragtime? Just because he was a ‘genius’? I think it’s because he had received these manuscripts with Scottish melodies from Thomson! George Thomson of Edinburgh was a civil servant, amateur musician, folksong collector, and publisher who commissioned 179 folksong arrangements from Beethoven. These arrangements, in my opinion, weren’t particularly interesting…because he had created them with rationality….but when what he had assimilated from those melodies, that is, the syncopated accents of Scottish music, came forth in an unconscious, spontaneous form, he created something incredible, Ragtime! And that is what I consider genius, the instinct, drawing on tradition to create something new and innovative. Genius is the one who lets the values of tradition pass through himself, transforming them. Beethoven’s ragtime can be heard here:

When Beethoven Invented Boogie-Woogie 100 YEARS EARLY!

Scottish music is the ancestor of Irish music, to which it gave various musical elements, melodies and forms, such as the reel, which is the most syncopated form of Irish music. Blues is a very good example, as a musical structure, of the most ‘African’ part of Jazz, and I think in particular it comes from Mali. But as a concept, the soul of Blues, which means ‘lament’, and turning sadness into joy, is the same as the Irish ‘Sean-Nós’ , the Flamenco ‘Cante Jondo’, an Indian ‘Mantra’, etc. At certain moments it means to detach oneself from personal sorrow, and to enter into a meditative state of universal understanding and fraternity. At other moments to transform suffering into joy in a festive and joyful manner, creating a celebration that surpasses death. The similarity of Irish funerals to those in New Orleans is not a coincidence! At the musical level, this concept becomes a primordial expression sung untempered, where the major and minor sounds are not separated, they merge, thanks to the modal system. Another important element is the one that unites all these peoples, which is expressed by the gypsy name ‘duende’: the contact with the spirit of the ancestors, contact with the source of life. Gypsy flamenco musicians consider music really great not when there is great technicality but when the spirit of the ancestors appears to them through music. All these factors are what ‘tradition’, and the true spirit of Jazz means to me.

As I look at your career I suddenly see instruments and trends, which are popular nowadays. In 1985 you concluded the International Jazz Festival of Poland together with south African pianist Dollar Brand, in the same year people could see thanks to you on TV cajón by Antonio Carmona de Los Abichuelas. It sounds quite a mystery for me, because nowadays we can see cajón everywhere – presenting it like an exotic instrument. Not to forget to mention pan flute player Gheorghe Zamfir and lots of others. As well we can see, the organizers of the festival “discover” nowadays the music of Africa – whether Southern or Northern (which are very different cultures) and also they introduce us the pan flute as something exotic. But you came with all these “fusions” years and years ago! So how all these your visions appeared? Sure, the genre of world music was popular in these years… How this music differ nowadays?

Thank you first of all for your kind words! I must say that seeing things first is not an advantage, because one often has to suffer and is not understood. My ideas often provoked scandal, and then became fashionable later on…. Having introduced instruments from different traditions is, let’s say, a fundamental concept to bear in mind, especially at this time of humanity. Exchange between peoples and cultures is necessary; if a culture closes itself off and preserves its tradition without exchanging, it dies. Conversely, if this exchange becomes an imposition from above, i.e. one country conquers another and erases its culture, it dies itself. For example, in the culture studied at school, in the relationship between Rome and Greece, it was not a bad relationship, in this case, when Rome conquered Greece, there is the famous phrase:“Graecia capta ferum victorem cepit” Which means “conquered Greece conquered its swaggering conqueror”, in the sense that Greek culture was stronger than Roman violence, Greek poets also became the poets of Rome, music and art won the battle.

One of the definitions I am most grateful to have been given is the one by the Basque poet J.A.Irigarai: “Mezulari” – which in Basque means messenger of peoples and cultures. Which is the same concept as the Tao of Lao Tzu, which is over 2000 years old: ‘I do not create, I pass on’. When we are at an Irish session or a session of gypsy musicians in Spain or Slovakia where we sing, dance and play all night, we are eternal, and there is no more time, death, religion or atheism, only eternity.

Harmony among the people – it is your different project. You became friend with the national Basque singer Benito Lertxundi. What is so fascinating about finding different cultures and different people? Do you consider your album Nomadic Aura significant for your musical journey?

Yes, my 1992 album Orekan, which means harmony between peoples in the Basque language, is one of my most important works. I tried to create a kind of ‘symphonic’ concept bringing together piano (the top classical instrument which started the new ‘well temperament’ system) with a vast variety of ‘not tempered’ instruments, belonging to many different ethnic traditions. Nomadic Aura is an album currently out of print; it was indeed very important for me, made for the city of Guernica, in the Basque Country, a project for world peace among peoples. I consider Guernica to be one of the few places that can have the right to talk about world peace, because during the Second World War it was one of the first to be bombed by the Nazi in Europe, but above all because the Basque people have been oppressed and have always fought for freedom and equality between peoples.I am honoured that the city of Guernica sponsored and produced this record, where various artists from the Basque Country, Ireland, Chile and southern Italy met together to work with me. Songs from this record have been included in new works, such as Samara, and various compilations.

You started to focus more on piano, beautiful sound, colours and cantilena solos of other instrument. We still feel it is jazz, because of the rhythm, structure, solos, but anyway, it has a cinematic mood. And of course, we can feel your significant style. How do you feel the progress and changes in your career?

You are actually right, 80 % of the music I make should be made for cinema. I have had many friendships with some of the greatest directors in Italy and abroad, but business is another thing! Friendship often does not go well with business! My most important and longest collaborations with theatre and cinema have been with film directors Folco Quilici, Franco Piavoli, Mario Monicelli, Ermanno Olmi, the Zappalà Danza company and actor Giorgio Albertazzi and theatre director Michel Poletti. All these were very important and significant works and collaborations, but they did not bring commercial success. So the progress and changes in my career, which, as you noted, should have been directed towards the world of cinema, have been there, but perhaps have yet to come more widely! The progress in my career so far has only been in the dimension that I was most interested in, the human dimension and the relationships with other musicians, with whom I have always shared life stories and deep friendships, and never have they been relationships dictated by business. And the relation with the extraordinary musical cultures these musicians came from, which produce the real music, the music that heals.

Your album Samara with well known musicians in the world – Máirtín O’Connor (accordion), Tony Byrne (guitar), Joe Mc Hugh (uilleann pipes, whistles), Paddy Cummins (mandolin, banjo), David ‘Hopi’ Hopkins (bodhrán) and your daughter, Consuelo Nerea (vocals, fiddle, bodhrán, harmonium) is again an interesting mix of cultures. We can find on this album your compositions, traditional Irish songs and one traditional tune. It is a mix of jazz, classical music and other influences of different styles of music. Does music have any limits for you? Because listening to your music from this album, it seems not really…

Thank you for your appreciation of my work ‘Samara’. I must say that although it is a mix, Irish music is always at the heart of this work.

https://open.spotify.com/intl-

Ireland for me is like an extraordinary meeting point between North, South, East and West, and you can hear this very well in the music. Tradition needs innovation, because innovation and contamination are natural elements of traditional music. In Ireland the music is still called ‘tradition’ like the New Orleans Jazz, just as in Bach’s time his music was not called classical music but ‘tradition’.

I’ll tell you a little story: one day accordionist Tony Mc Mahon, who is amongst one of the most important and severe purist traditional Irish musicians, organised for me a gig in a very intimate venue, known to be the venue for traditional purist musicians. He had a big respect and admiration for my work that was quite the opposite, it was contamination. At the time, when terms like World Music still didn’t exist and it was not a fashionable thing to do, many people would think I was crazy. There was that night a great purist traditional piper, Peter Brown who was working with Tony for the Radio, who was going to share the concert with me. Unfortunately Tony couldn’t be there that night because he had a last minute emergency, and so he couldn’t introduce me properly to Peter, who didn’t know me. When Peter saw the grand piano on stage he was almost embarrassed, because he was very purist, and a bit of a snob, and he didn’t understand what that instrument had to do with Traditional Irish music. So before the gig he told me quite coldly: “You know…Irish traditional music doesn’t need contaminations.” I answered:“You are right Peter, because it’s already so contaminated!” He was almost scandalised, and I added: “yes of course, cause traditional Irish music, even the most ancient “pure” one, is also in some way Chinese, Indian and African. Depending on the tunes and the songs, you can find so many influences from different cultures very far away from this island. Irish music is already contaminated, and I was certainly not the first one to contaminate it! I will try to explain this in more detail: In the natural development that traditional music had during the centuries, contaminations always happened, but these contaminations were filtered through time, often centuries. This makes it one of the most complex, developed, and “living” traditional music in the world. We can’t really talk about “the original” traditional Irish music, cause this is a music that has been constantly evolving through centuries, and what we have today is very different from what was played in Ireland 500, or even 200 years ago. This is the natural course of a “living” traditional music: innovation and contamination are integral parts of it.

Songs and tunes travelled around Europe in the mediaeval times, Irish monks and pilgrims would travel all around being in contact with so many different cultures, bringing the Irish culture to Europe, and bringing back other influences from all the places they visited.

It is known that there was a big exchange between Italian composer and violinist Geminiani and Irish composer and harper O’ Carolan in the 17th century and the influence of Italian Baroque music it’s clear in the work of O’Carolan.

Studies about the connections between Irish Sean nos singing and Arabic chant are fascinating and tells a lot about what we always forget: we are way more connected and “contaminated “ than what we would think. Irish music also has incorporated a big variety of instruments from other cultures: if we look at the original instruments, we would have only harp and vocals. The uilleann pipe came after, as a development of the Scottish bagpipes (but the ultimate origins of this instrument trace back to Egypt). Then they incorporated the fiddle, bodhrán, flutes and all the other instruments, many of which, like accordion, concertina, guitar, only arrived in recent times ( late nineteenth or twentieth century), and the bouzouki only in the late 60s (borrowed from Greece). Today we see a new instrument being adopted by traditional Irish music: the harmonium, an Indian instrument with French origins.

I would never think this combination of instruments could work together. And listening to accordion I finally found, it really can sound beautiful and it has a sense in a group with other instruments! And it has a special affinity to piano. You already work with Máirtín O’Connor before this album. Is it important for jazz musicians to feel each other, to know the process of musical thinking?

Absolutely, listening to each other is fundamental, but also and above all exchanging life experiences together, it’s important for musicians of any genre, otherwise music is not alive. As I was mentioning before, all these extraordinary and countless musicians, which have been and still are collaborating in my albums and concerts, have almost never been doing it only for work. With most of them I shared strong stories of life and real friendship, I still cannot believe how many.I can’t think of rationally doing a collaboration in a month, for business purposes, like it happens many times today with artists who can afford thousands of euros to pay musicians to create a “collaboration”. Especially if the only aim is to “follow the trend”, “sell a product”… make more money. I’ve been interacting with traditional musicians from many cultures all my life. My instrument, the piano, wasn’t a traditional one, I wasn’t born in Ireland or Spain and my background was Jazz and classical music. But my spirit was somewhere else…with the gipsies and the Irish traditional musicians… so I had to communicate with these musicians and we found our common language!

And finally we could say in the end of this interview something about your concert in Liptovský Mikuláš, in Slovakia, where the jazz audience will have a possibility to see you. You know Slovakia or it would be your premiere here? What did you prepare for us? Any surprises at the concert?

Two years ago we were invited to perform in Slovakia, precisely in Presov, and we attended the festival Rozhybkhosti in the mountains, which was an unforgettable experience.

Here dancing and singing all night till dawn I felt the same spirit of the ‘duende’ of the flamenco tradition and the sean nós of the irish tradition. I felt immediately at home!

What today is called globalisation is the exact opposite of exchange; man should have moved towards respect for minorities, individuality and love for others, instead he moved towards individualism and flattening! In Slovakia, I immediately felt that this was a people who had maintained identity but also respect for others.

As for the programme…this is always a surprise for us too! But above all… it depends on you, on the energy of the audience, because I believe that 70 per cent of the music in a concert depends on the interaction between the audience and the musician, who is just a vehicle. As an old Arab proverb says: “words belong a little bit to the speaker and a little bit to the listener!”

And finally the last question: Your music is also used for therapy. You personally did music laboratory for handicapped, homeless, drug addicts. Do you believe music can help for body and mind of people? I do not want to say it can heal a people, but definitely at least help in the process…

For me, the concept of music therapy is quite complex, and should not even exist. Music either cures and is therefore therapy in itself, or it poisons. There is no such thing as neutral music. People say ‘I like this music, so that means it’s good for me’, but that’s not the case…

95 % of the music that people listen to today is conditioned by the mass media and the big music business, it is chosen by them! People think they choose, but in reality they are subservient to a system that chooses for them. But people, when confronted with music that is therapy, recognise it, so the goal of any true musician today should be to cultivate and spread this music, even if the risk is to stay out of the business. Yes, I did a lot of music therapy work with Italian immigrants in Switzerland. At a time when political song was so popular, I was a bit critical of it because it had become a fashion. Even Victor Jara shortly before he was killed during the coup d’état in Cile because of what he was singing said: “I am fed up with the political song, today there is the Hit Parade of the political song, a real love song is a political song.” My goal was to make Italians re-appropriate the revolutionary rhythms and melodies of their traditions, for example rhythms that bring back socialisation, dance (not the neurotic shuffling dance of a mega-concert in a stadium) and sense of community.

Music that unites all ages, because this is another fundamental problem of today’s rootless music, which divides by age categories. This is in my opinion the only thing that can fight what the system calls drugs, and certainly not the other musical and television drugs that are fed. I try to convey a connection with the roots for those almost dry trees, roots that are common to all the music in the world and without which music becomes just a drug, a toxic food full of dyes and hearing enhancers that poisons the body and the soul… because as I wrote in my book ‘Heyoka’: ‘There is a lot of talk today about music as therapy but little about music as intoxication!’

I would like to end with this other phrase from the same book: ‘Music is considered today as a sublime art or as a trivial product of consumerism. We have completely forgotten that it used to be simply a part of life.’

Thank you for this interview!

Zuzana Vachová

TItel photo: Milena Giacomazzi